Photo by Bernd Klutsch on Unsplash

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11866151/

Gilbert’s syndrome: The good, the bad and the ugly

Arjuna Priyadarsin De Silva 1, Nilushi Nuwanshika 2, Madunil Anuk Niriella 3, Hithanadura Janaka de Silva 4

Gilbert’s Syndrome the Good the Bad and the Ugly is a summary of research about Gilbert’s Syndrome published between 1977 and January 2024. It’s great to see some attention paid to pulling together a range of information on this important condition. What is also clear is how many gaps there are in our understanding of Gilbert’s Syndrome.

To make it easier for people to access the information I’ve summarised it below, and follow up with a critical look at the article. I hope this helps you better understand Gilbert’s Syndrome.

Here’s the summary:

What Is Gilbert’s Syndrome?

Gilbert’s Syndrome (GS) is a common genetic condition where the body has trouble processing a substance called bilirubin. Bilirubin is made when the body breaks down old red blood cells. Normally, the liver changes bilirubin into a form that can be removed from the body, but in people with GS, this process doesn’t work well. As a result, bilirubin builds up in the blood.

How Common Is GS?

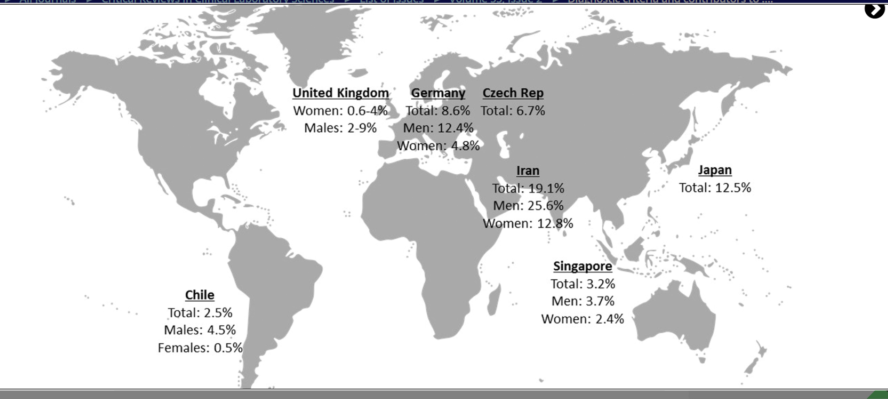

GS affects around 2% to 13% of people, depending on their race or ethnic background. It is more common in:

- South Asians: up to 20%

- Middle Eastern people (e.g., Iranians): about 19%

- Caucasians (Europeans): 2-10%

It is also found more often in men than women.

Is GS Dangerous?

No, GS is usually harmless. It doesn’t cause liver damage, and people with GS usually live normal, healthy lives. In fact, some studies suggest that people with GS may even live longer than average.

How GS Affects the Body

What Happens in the Body?

In GS, the liver doesn’t produce enough of an enzyme called UGT (short for UDP-glucuronosyltransferase). This enzyme helps change bilirubin into a safer form the body can get rid of. Without enough UGT, unprocessed bilirubin builds up.

People with GS may sometimes appear a little yellow, especially in the eyes or skin. This is called jaundice. It usually happens when the person is sick, tired, not eating enough, or stressed.

Why Do People Get GS?

GS is inherited, meaning it is passed down from parents to children. The gene responsible is called UGT1A1. Changes in this gene cause the liver to make less UGT enzyme.

Different genetic changes happen in different parts of the world. For example:

- In Europeans, a common change is adding extra TA repeats in the gene.

- In Asians, a different change called Gly71Arg is more common.

Symptoms and Diagnosis

What Are the Symptoms?

Most people with GS don’t have any symptoms. Some may notice:

- Slight yellowing of the eyes or skin (especially during fasting or illness)

- Feeling tired or weak (less common)

There is no pain, no itching, and no change in stool or urine color.

How Is GS Diagnosed?

Doctors often find GS by checking blood tests and ruling out other liver problems. Important signs include:

- High unconjugated bilirubin levels

- Normal liver function tests

- No signs of blood breakdown (no hemolysis)

Sometimes, special tests like fasting or medicine tests are used to confirm the diagnosis.

Living With GS

Do You Need Treatment?

No treatment is needed for GS. People with this condition:

- Don’t need medicine

- Don’t need special diets

- Should just be aware of their condition

The most important thing is reassurance. GS is not dangerous and does not become a serious disease.

When to Be Careful

Doctors and patients should be careful not to mistake GS for a liver disease. This can lead to unnecessary tests or worry. It’s important to recognize GS early to avoid confusion.

Critical Analysis of “Gilbert’s Syndrome: The Good, the Bad and the Ugly”

The article offers a broad and largely well-researched overview of Gilbert’s syndrome (GS), including its epidemiology, genetics, clinical manifestations, and broader systemic associations. A few areas could do with further scrutiny and contextual comparison with current literature to enhance clarity, clinical relevance, and scientific accuracy.

The article contradicts itself and other research. The authors maintain that you shouldn’t be concerned about GS and yet list a number of chemicals to which toxic responses may be a problem, and the article fails to include some common drugs such as statins. There may especially be issues for pregnant people or people with schizophrenia – but the connections aren’t clearly articulated.

Gaps include reference to common symptoms – study finds that there is no abdominal pain, for example, however other studies eg https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30717703/ have associated GS with this. Many of this website’s readers and myself have all experienced pain in the upper right quadrant of the abdomen. Other common symptoms that impact people’s lives include brain fog, nausea, itching and anxiety.

As ever, there is so much more that could be covered!

Strengths of the Review

1. Balanced Overview of Pathophysiology

The article correctly identifies UGT1A1 gene polymorphisms, such as the (TA)₇ repeat and UGT1A1*6 (Gly71Arg), as the main culprits in reduced bilirubin conjugation. This aligns with Bosma et al. (1995) and later studies confirming these variants’ functional impact on UGT1A1 expression.

- ✅ Strength: Ethnic variability is well-described, reflecting differences in allele prevalence between Western and East Asian populations.

- 🔎 Opportunity for more depth: The article could benefit from deeper discussion of linkage disequilibrium and the impact of compound heterozygotes, which can alter the GS phenotype ie. other chromosomal or gene differences that can exist alongside Gilbert’s Syndrome, and change how it works.

2. Integration of Protective Effects

The article thoroughly explores the antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties of unconjugated bilirubin. Recent meta-analyses (e.g., Zhou et al., 2022; Vítek, 2020) support the protective role of mildly elevated bilirubin levels in reducing risks of:

- Cardiovascular disease

- Metabolic syndrome

- Certain cancers

The claim that each 1 mmol/L increase in bilirubin correlates with a 6.5% reduction in cardiovascular risk is based on credible sources (e.g., Zucker et al., 2004; Vítek & Ostrow, 2009).

- ✅ Strength: The inclusion of concrete risk reduction statistics makes the article clinically relevant.

- ⚠️ Limitation: It should have critically assessed whether elevated bilirubin is causal or merely a biomarker of lower oxidative stress. Recent Mendelian randomization studies suggest causality may be modest at best (e.g., Liu et al., 2021, JAMA Cardiol).

Weaknesses and Limitations

1. Lack of Critical Appraisal of Confounding Factors

The article doesn’t sufficiently evaluate confounding variables in studies associating GS with reduced morbidity and mortality. For instance, individuals with GS often have:

- Lower body mass index (BMI)

- Favorable lipid profiles

- Healthier lifestyles

These may confound the purported protective effect of bilirubin. This has been pointed out in Boon et al. (2012) and Zheng et al. (2019), who note that associations weaken significantly after adjusting for confounders.

2. Schizophrenia Section Lacks Causal Clarity

The article suggests a potential link between GS and a more severe form of schizophrenia, citing changes in brain metabolites and MRI signals. However:

- These findings are not widely replicated in the psychiatric literature.

- No mechanistic explanation or longitudinal data supports this claim.

A study by Celik et al. (2014) hinted at altered brain chemistry in GS patients with schizophrenia, but sample sizes were small, and methodology limited. Without replication, this remains speculative.

- ⚠️ Concern: The article presents this association too strongly without clearly emphasizing that causality has not been established.

Overstatement of Therapeutic Implications

The notion of “iatrogenic GS” via pharmacological UGT1A1 inhibition as a therapy for MASLD is intriguing but premature:

- Animal models show some promise (e.g., Hinds et al., 2020), but this strategy has not progressed to human trials.

- Inducing GS pharmacologically could lead to drug toxicity or hyperbilirubinemia-related complications, especially in neonates or pregnant women.

The review lacks a clear risk-benefit discussion of such interventions, which is essential for any proposed therapeutic model.

Clinical Utility and Real-World Application

The article rightly emphasizes avoiding unnecessary testing in asymptomatic hyperbilirubinemia. This aligns with the principle of “Choosing Wisely”, and echoes guidelines from hepatology societies. However:

- It could more clearly highlight the need for differential diagnosis in non-classical presentations (e.g., persistent jaundice, transaminitis, hemolysis), ensuring other possible conditions are ruled out before diagnosing with Gilbert’s Syndrome.

- It should caution against overreliance on bilirubin levels without genetic confirmation, especially in mixed-ethnicity populations.

- Further consideration should be given to understanding why some people with Gilbert’s Syndrome have symptoms and why others don’t, using the information such as genetic variation and lifestyle factors to understand this.

Drug Metabolism Section: Well-Considered but Needs Expansion

While the review touches on key drugs affected by UGT1A1 metabolism (e.g., irinotecan), it omits:

- Emerging drug-gene interactions in pharmacogenomic databases like PharmGKB, which include a wider range of UGT1A1 substrates.

- A more systematic classification of drug types (e.g., antiretrovirals, statins, antiepileptics) would enhance clinical utility.

- Given this is one of the most important consequences of having Gilbert’s Syndrome, both clinically and in terms of managing the symptoms, it has long been a frustration of mine that there aren’t more studies exploring which chemicals are processed differently. We are exposed to many different substances on a daily basis, and interactions with paint or petrol fumes, common cold remedies with menthol and paracetamol, solvents, perfumes and other cosmetics etc etc which may be processed differently with Gilbert’s Syndrome.

Conclusion: Solid Foundation, but Nuanced Critique Needed

In Summary:

| Aspect | Assessment |

| Scientific Rigor | Generally strong, particularly in genetic and metabolic domains |

| Clinical Applicability | High for primary care and hepatology, but some therapeutic ideas are premature |

| Gaps and Oversights | Confounding factors, schizophrenia link, iatrogenic GS risks |

| Recommendations for Improvement | More critical analysis of causality, clearer differentiation of evidence levels |

Final Verdict:

This review is a robust and comprehensive synthesis of GS literature, but it occasionally conflates correlation with causation, and it should more critically examine weakly supported associations (e.g., schizophrenia, therapeutic GS induction). Its strength lies in summarizing the current state of knowledge, but future iterations should differentiate more clearly between hypothesis, association, and proven benefit

And just a final comment – like much of the medical information you find about GS, the focus is on the presentation of raised bilirubin levels. This in itself is just one symptom, yet GS is often characterized as a disorder of biirubin metabolisation only. Bilirubin is just one notable element that is impacted by the lack of the UGT1A1 enzyme. ‘Uridine-diphosphoglucuronate glucuronosyltransferases (UGTs) are a family of enzymes that conjugate various endogenous and exogenous compounds with glucuronic acid and facilitate their excretion in the bile.’ although ‘Bilirubin-UGT(1) (UGT1A1) is the only isoform that significantly contributes to the conjugation of bilirubin.’ hence the focus on bilirubin in particular. But it is a mistake to look past the other compounds affected as mentioned – crucially some very commonly prescribed medications, as well as chemicals in the environment.